You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I tell you, resist not an evil person.

-Matthew 5:38-39

From the sayings of the desert Fathers

The brethren came to Abba Anthony and said to him, “Speak a word; how are we to be saved?” The old man said to them, “You have heard the Scriptures. That should teach you how.” But they said, “We want to hear from you too, Father.” Then the old man said to them, “The Gospel says, ‘if anyone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also.’ ” They said, “We cannot do that.” The old man said, “If you cannot offer the other cheek, at least allow one cheek to be struck.” “We cannot do that either,” they said. So he said, “If you are not able to do that, do not return evil for evil,” and they said, “We cannot do that either.” Then the old man said to his disciple, “Prepare a little brew of corn of these invalids. If you cannot do this, or that, what can I do for you? What you need is prayers.”1

I have always felt that one of the most significant contributions the teachings of Jesus made to the world, especially the West, was his insistence on radical non-violence. Not only in his sermon on the mount, but also in the ignominy of his death, and the serenity with which he endured such trials. In the end, among Christ’s final words are not the cry of what we might expect the Pantokrator (All-mighty) God to say. Which is to say: destroy his adversaries. Rather, we hear a softly uttered plea: “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do.”2 In ten words Jesus is able to encapsulate the heart of his teaching. In his very elevation on the wood of the cross Christ’s only concern is for those who, out of ignorance, have so savagely ravaged his body.

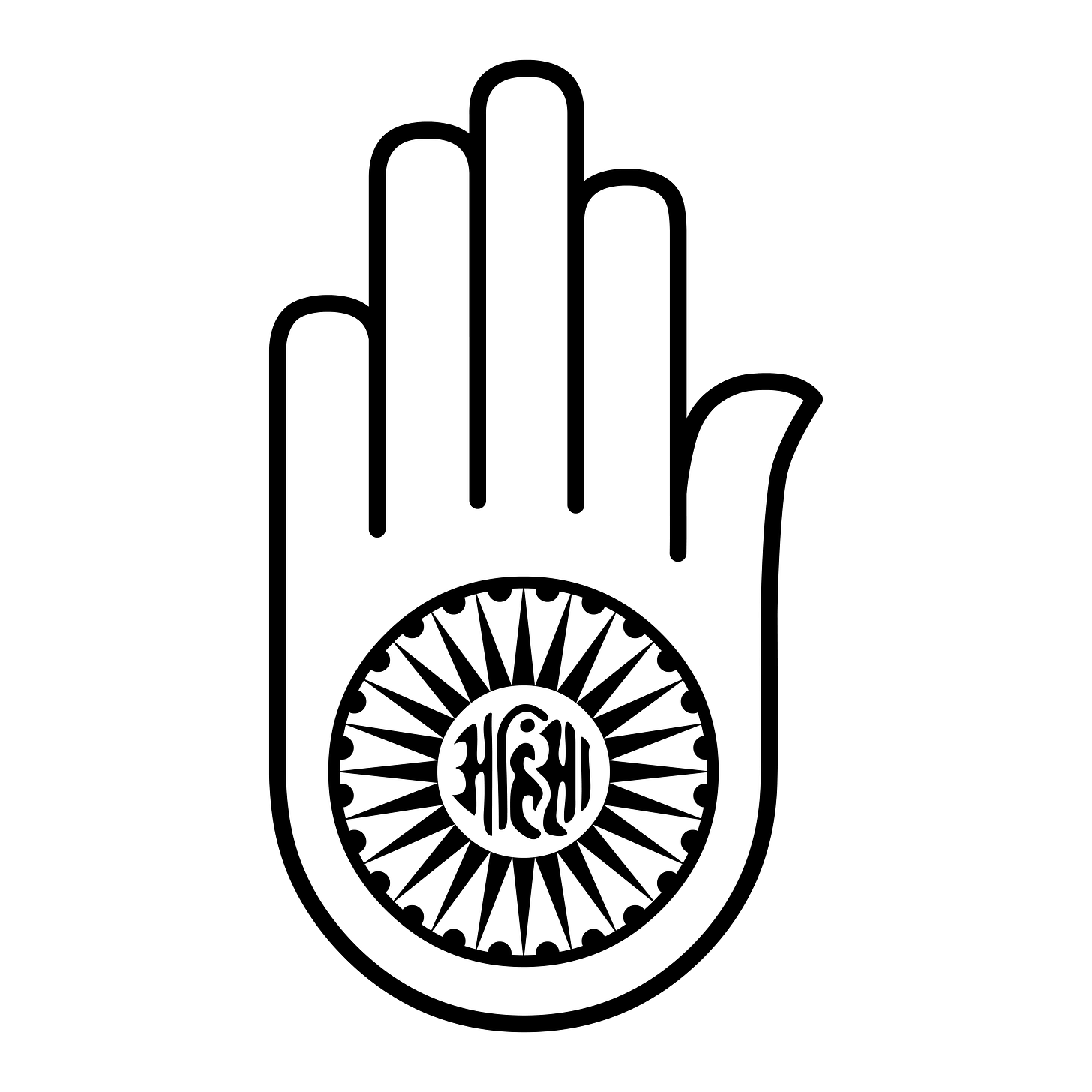

Perhaps it is in light of this radical commitment to non-violence that the kinship between Jainism, or rather Jain Dharma, and Christianity lay.

I pressed the doorbell, a flat rectangular thing, and waited a moment. The front door buzzed and lazily swung inward as someone electronically let me in. I stepped inside. Christ House: a beacon of hope for homeless men in the District. The drab grey and taup walls were shabby from years of use not helped by the clinical lighting, but everything was clean and tidy. This was, among other things, a medical facility for the most vulnerable of our society, so cleanliness is key.

I walked down a long narrow hallway whose walls are decorated by art and poetry mostly made by patients in the clinic. A calligraphic interpretation of the serenity prayer features prominently. Notably, on my left, a large hazy orange portrait features a nautilus making it’s golden-ratio spiral all the way around the interior of the painting. Littered within the spiral are verses from numerous religions—all variations on the theme “do unto others.”

Hurt not others in ways that you yourself would find hurtful.

-Udana-Vargu 5.18

No one is a believer until you desire for another that which you desire for yourself.

-Sunnah

Be not estranged from one another for God dwells in every heart.

-Sri Guru Granth Sahib

In happiness and suffering in joy and grief regard all creatures as you would your own self.

-Lord Mahavira 24th Tirthankara

This final quotation was striking to me. In part, because while the various verses all had to do with treating others as you would treat yourself, this was the only verse that seemed to, with shocking clarity, extend this ethical principle not only to other humans, but to all living beings. I always knew Jainism to be an irenic religion. I have been fascinated by these monastics who, with careful deliberation, gently sweep in front of wherever they’re walking so as to avoid disturbing or killing small insects and other microorganisms. Often, they even wear a thin veil over their mouth and nose to avoid possibly even injuring an insect by their breath.

I think we can safely say, no other religious group has such a radical commitment to not causing even the slightest harm to any organism no matter how big or small.

They embody the lesson from that great philosopher Horton “A person’s a person no matter how small.”

However, within the Christian faith, this impulse is also quite strong. In fact, at various points throughout the sermon on the mount, Jesus makes it clear that those who seek the kingdom must relinquish any claim on violence. Rather, the only violence we are to enact is a kind of spiritual violence, “For the Kingdom of Heaven suffers violence, and the violent take it by force.”3 This type of “mystical violence” is not so different from the Muslim jihād an-nafs, or “the struggle against ego” which emphasizes the oftentimes violent struggle against the many passions that war against us.

In the course of the sermon on the mount we are given the common or current understanding of the law, that is to say, what “has been heard.” Jesus claims that we have heard of the law of “An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth”4 but then declares “Not to resist an evil person.”5 We are also told to “Turn the other [cheek].”6 Our common, fleshly, understanding of the law is being transfigured so that the higher, spiritual, understanding can flourish. This non-violent attitude extends not just to our physical bodies, but also to any forms of injustice we suffer.

If anyone wants to sue you and take away your tunic, let him have your cloak also. And whoever compels you to go one mile, go with him two […] I say to you, love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you, that you may be sons of your Father in heaven; for He makes His sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust.7 (emphasis mine)

To be a follower of Christ, that is to say: to be a son of God, is not only not responding to violence with violence, but rather to bless, pray, and do good to those that hate us. In the Paschal Canon, written by Saint John of Damascus, we are called by the power of the resurrection to “Call brothers even those that hate us, and forgive all by the resurrection.”8 Christ reminds us that even those who hate us and spitefully make use of us are still beloved and sacred creations of the Most High. They are loved and adored with the same infinite and incomprehensible love that we ourselves are loved by.

Therefore, in Christ, violence can be no more. For all violence has been absorbed by the dead naked Theanthropos9 on the cross.

Even with this in mind, the impulse towards non-violence, which is undoubtedly an integral part of the Christian religion, has and remains fairly unpopular. The centuries of past bloodshed extend even to our present day, caused by those who manipulate the Gospel, and call for something like a Christian “Holy war.” As if, in any meaningful way, this absolute and utter contradiction is not impossible from the outset. More immediately, as we zoom in on our personal lives, the law of the jungle to bite and tear at one another for injuries real or perceived is irresistibly strong. All too often, our impulse is to “get back” to “settle the score” to bend and twist notions of “justice” by killing, harming, or exacting vengeance on those who have hurt us or our community.

But the great Tirthankara10 Mahavira with our Christ gently points us in another way,

In happiness and suffering in joy and grief regard all creatures as you would your own self.

Mahavira himself lived this principle on his journey to kevala jnana (supreme knowledge) by allowing insects to crawl on and bite him without responding with aggression. His life and teaching are an extremely high calling for us to lay aside our personal cares and elevate concern for the other in every way. It is to forgo, as Jains do, the pleasure of meat and all animal products11 out of an abundance of compassion for all creation. It is to attempt to confront and heal the brute fact that “jīva lives by devouring jīva.”12 Perhaps it is a real manner of walking in faith, contrary to our fleshly and fallen understanding and regain that primal bliss in which God and Mankind walked in harmony together in the garden.

Ahimsā, non-violence, becomes then the outline for the entirety of Jain, and I would argue Christian life.

The five great vows (mahavatra) of Jainism flow from and back to their source in ahimsā.

They are as follows:

Ahimsā: Non-violence

Satya: Truth

Asteya: Non-stealing

Brahmacharya: Chastity

Aparigraha: non-possessivness

Each vow is, in reality, a further unfolding of the chief principle: ahimsā. Whether it be telling the truth, not stealing, chastity, and being non-acquisitive each opposing vice entails violence in one way or another.

Lying is a violence against the fundamental nature of reality. It is knowingly presenting a reality that you know to be, in matter of fact, false. It is an effort to manipulate a situation to benefit yourself to the detriment of others. Satya is not merely “not lying” but rather about presenting the totality of yourself, any given situation, and ultimately Reality as fully and wholly as you can with compassion. To steal is obviously an injury to another, especially when perpetrated against the poor who already suffer so much. It also involves the withholding of what another is due. This even includes the responsibilities we have towards others. To be unkind to your wife is not evil only in the sense that you are treating her cruelly, but also because she is deserving of your kindness. You have a duty to love your wife. Anything less than that total martyric devotion is theft of the spiritual and emotional energies owed to her. The unchaste person damages not only the other by their rapacious sexual appetites, but also themselves (and we do bear a tremendous responsibility not to harm ourselves by vice). They exist in a state of division in which they view others not as subjects, but as objects, and by extension even themselves as objects. Therefore, the unchaste person is not necessarily to be thought of only as a Don Juan of sorts. Rather, failure to uphold brahmacharya leads to an individual who cares more about the facts of a person as opposed to their intrinsic personhood. It is a terrible reduction of the image of God into a mere coalescing of facts and history. Finally, the acquisitive person is a person who lives their life in fear. A fear that they will lack what they need. They do harm to others precisely by their inability to let go. The wise saying of Saint Basil “The extra coat in your closet belongs to the poor”, for the acquisitive person, takes the form of an existential threat.

And while not a vow, a unique application of ahmisā exists in the form of mental or philosophical ahimsā known as anekāntavāda or “many-sidedness.” As each mahavatra entails an intrinsic non-violent outlook, so to with anekāntevāda. It is a belief, or rather, a principle by which to live by, in which ultimate reality can never truly be pinned down with any discursive syllogism or clever turn of phrase. It is not a relativistic outlook, but rather a profound application of both aphophaticism and ahimsā. Where to know who and what God is is not something to be grasped, but a living relationship to be experienced.

My relationship with Jain Dharma rests less in a sense of fascination with a unique philosophy that offers complementary explanations for the mysteries of Christian life. Rather, in the encounter between Christianity and Jainism rests a rather salutary dialogue in which we Christians have much to learn, or rather remember.

The story of Abba Anthony highlights that the “Gospel”, literally the good news, is Jesus’ teachings on non-violence. Christ’s dharma can perhaps be summarized as succinctly as “non-violence.” In every step the Lord took He exuded the Spirit of peace. In healing the sick, giving sight to the blind, restoring hearing to the deaf, and opening the mouths of the mute, He overcomes the violence of sin. In His ultimate outpouring of radical, self-emptying, all-ravishing love we see the lengths God will go to walk the hard path of non-violence for he is “a man of sorrows.”13

I perhaps yearn for that primitive, certainly romanticized (although if our Christianity is not idealized it is likely on the verge of death or total corruption by a loathsome pragmatism), Christian movement in which the radicality of Christ’s all-encompassing victory over death frees us from the sting of death which is sin, granting us the courage for non-violent living. There is no death, we now no longer have any excuse or license for violence. In his death, we find life, and we no longer sin for fear of death.

It is true, we sin—commit violence, lie, steal, behave licentiously, and succumb to avarice out of fear that maybe this is it. Maybe our small, insignificant lives on a tiny blue marble hurtling through space awaiting the heat death of the universe is all there really is. The facts are: we are born, we suffer greatly, and we die. And if that’s all there is then we better get what we can while we can.

But in faithfulness to Christ can the lotus of true ahimsā push through the muck and mire of life and blossom into a truly life-giving and blissful existence free from the constraints of fear of death and the harm done to us. When we read the teachings of Christ, the only sane way we can do so is through the lens of non-violence. The early Church knew this. She died for this. The blood of countless bear witness (μάρτυς)14 to this revolutionary insight. If our faith is real, if it is to be something more than mere beautiful words we must live by this principle:

In happiness and suffering in joy and grief regard all creatures as you would your own self.

Benedicta Ward, Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Trappist, KY: Cistercian Publications, 1975. 5.

Luke 23.34

Matthew 11.12

Exodus 21.24

Matthew 5.39

Ibid.

Matthew 5.40-41, 44-45

Priest John Mikitish and Hieromonk Herman, Orthodox Christian Prayers, South Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon’s Monastery Press, 2019. 268.

Lit. God-Man

Lit. Ford maker. One who has crossed the interminable sea of samśara and the endless cycle of death and rebirth and has made a way for humanity to liberation by his dharma.

As well as all root vegetables such as garlic, onions, potatoes, carrots, etc. because of the harm it causes to microorganisms and small insects.

In dharmic faiths jīva is being with life-force. It is closer in understanding to the “soul” as we typically understand it. In Hinduism it is often, although not always, distinguished from Atman, the Self, which itself can be understood more as that deepest self that is associated and connected to the Supreme Self (Brahman).

Isaiah 53.3

The word “martyr” coming from the greek martys means “witness.” The martyrs then are considered witnesses to the faith in spite of their many trials.