Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence and if anything worthy of praise, think about these things.

-Philippians 4:8

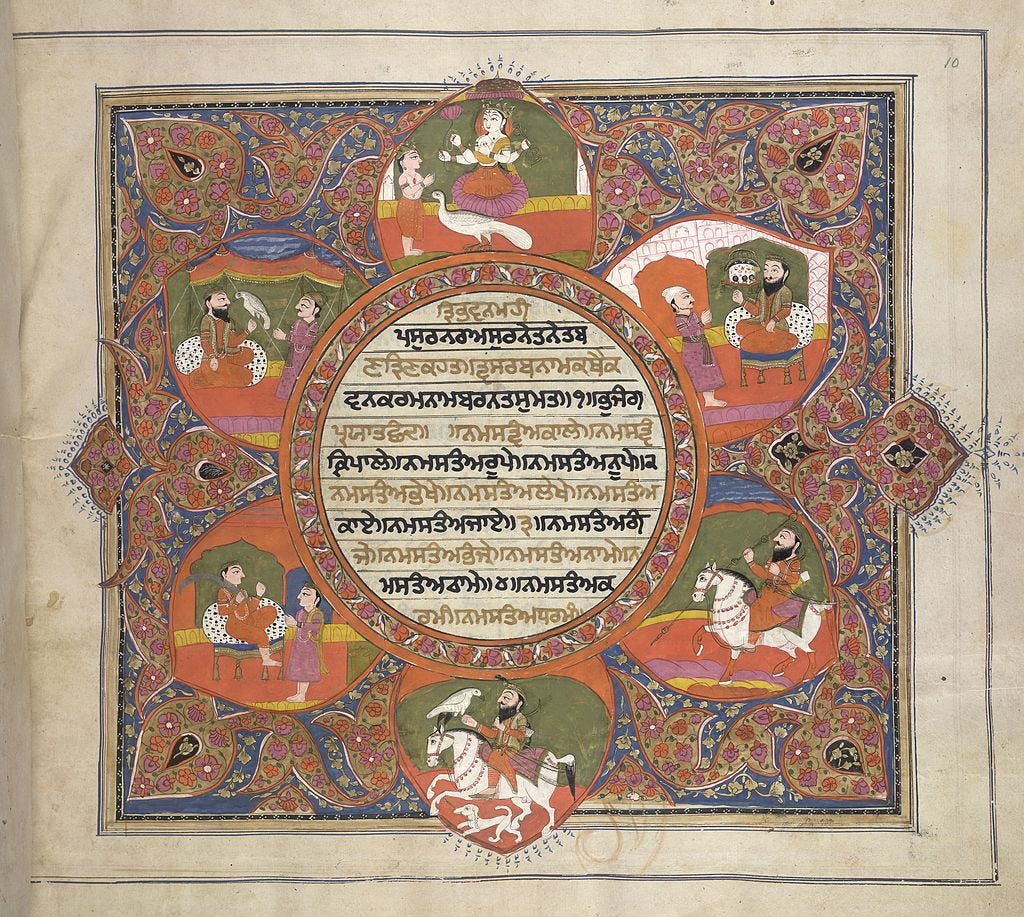

All the prophets have from the beginning cried out to my soul, imploring her to make herself a virgin and prepare herself to receive the Divine Son into her immaculate womb;

Imploring her to become a ladder, down which God will descend into the world, and up which man will ascend to God;

Imploring her to drain the red sea of sanguinary passions within herself, so that man the slave can cross over to the promised land, the land of freedom.

The wise man of China admonishes my soul to be peaceful and still, and to wait for Tao to act within her. Glory be the memory of Lao-tse, the teacher and prophet of his people!

The wise man of India teaches my soul not to be afraid of suffering, but through the arduous and relentless drilling in purification and prayer to elevate herself to the One on high, who will come out to greet her and manifest to her His face and His power. Glorious be the memory of Krishna, the teacher and prophet of his people!

The royal son of India teaches my soul to empty herself completely of every seed and crop of the world, to abandon all the serpentine allurements of frail and shadowy matter, and then--in vacuity, tranquility, purity and bliss--to await nirvana. Blessed be the memory of Buddha, the royal son and inexorable teacher of his people!

The thunderous wise man of Persia tells my soul that there is nothing in the world except light and darkness, and that the soul must break free from the darkness as the day does from the night. For the sons of light are conceived from the light, and the sons of darkness are conceived from darkness. Glorious be the memory of Zoroaster, the great prophet of his people!

The prophet of Israel cries out to my soul: Behold, the virgin will conceive and bear a son, whose name will be — the God-man. Glorious be the memory of Isaiah, the clairvoyant prophet of my soul!

O heavenly Lord, open the hearing of my soul, lest she become deaf to the counsels of Your messenger.

Do not slay the prophets sent to you, my soul, for their graves contain not them, but those who slew them.

Wash and cleanse yourself; become tranquil amid the turbulent sea of the world, and keep within yourself the counsels of the prophets sent to you. Surrender yourself entirely to the One on high and say to the world: “I have nothing for you.”

Even the most righteous of the sons of men, who believe in you, are merely feeble shadows which, like the righteous Joseph, walk in your shadow. For mortality begets mortality and not life. Truly I say to you: earthly husbands are mistaken when they say that they give life. They do not give it but ruin it. They push life into the red sea and drown it, and beforehand they wrap it in darkness and make it a diabolical illusion. There is no life, O soul, unless it comes from the Holy Spirit. Nor is there any reality in the world, unless it comes down from heaven.

Do not slay the prophets sent to you, my soul, for killing is only an illusion of shadows. Do not kill, for you can slay no one but yourself.

Be a virgin, my soul, for virginity of the soul is the only semi-reality in a world of shadows. A semi-reality—until God is born within her. Then the soul becomes a full reality.

Be wise, my virgin, and cordially receive the precious gifts of the wise men from the East, intended for your Son. Do not glance back toward the West, where the sun sets, and do not crave gifts that are figmental and false.1

In the course of doing this kind of work, which is to say the kind that entails reading copious amounts of non-Christian literature, one need not receive external admonition that there is something suspicious and potentially dangerous about this endeavor. Indeed, many have strayed from the straight path in their pursuit of knowledge for it is written “Knowledge puffs up.”2 However, it is in humility, and the knowledge that I journey along well-trod paths, that I do happily read and write away on this topic fraught with many temptations. It needs no longer be written where my religious commitments lay. But when I sometimes doubt my own intentions and the direction I am taking, I find that perusing the writings of great teachers and wise men from Orthodoxy I am not only nourished spiritually as a Christian but am also encouraged to continue to engage in this kind of work. St. Nikolai’s prayers by the lake are themselves sufficient nourishment and refreshment to encourage me as I continue to study and write on these sundry topics related to perennialism, and make liberal use of the wisdom and imagery from beyond my Christian pasture.

This particular prayer is shocking. Scandalous even, I might add. The holy Nikolai is drinking about as deeply from the well of perennial philosophy as any other when he composed such a marvelous ode of celebration to the teachers and (as he writes) prophets of non-Christian religions. Reading the prayer could lead to the conclusion that he is perhaps a new-age guru seeking to lead his students into an appreciation of the Unity of God and that all spiritual paths lead to one and the same place. And yet, as we know from the rest of St. Nikolai’s life, this is not the case. Or rather, he did envision all paths pointing to one place: the Incarnate Christ. He was himself a staunch supporter of Orthodoxy who labored diligently from the first hour in the vineyard of the Lord becoming not only a great saint of the Serbian people and a light in the darkness of communist suppression of religion, but a redolent flower of Orthodoxy in modernity.

What is perhaps so shocking (and for my purposes so instructive) about this prayer is that it is decidedly unashamed in the language it uses to sing praises to the prophets and teachers of other religions and philosophies. One could, in theory, go down a long list of teachers, messiahs, prophets, gods, and demigods and describe what aspects of their teaching is most useful. However, beyond an aesthetic appreciation for the sentiment this prayer evokes, I think the attitude exemplified in this prayer is helpful in giving us a set of guidelines for what is a safe and conscientious manner of engaging in perennial discussion and inter-faith dialogue. The ecumenical movement that began among protestant churches in the 20th century has now grown into a full assortment of summits, talks, and conferences where men and women of all religious traditions attend and discuss their faith. This is, in my estimation, a generally positive development in the history of world religions. While the history of inter-faith dialogue is not new, our capacity to share, meet, and discuss with the other is now more possible than ever before. As barriers for understanding have been razed, so too has our fear and suspicion of the other.

However, while these are undeniably an exceptional result of globalism, the internet, and easy access to information, this has also created a time in which religious confusion has never more been so pronounced. With ease does one enter a bookstore and find a text about unlocking one’s inner kundalini energies with the aid of astrology, vipassana, and Rumi. Such a smorgasbord of religious convergence rather than being ennobling often confuses and stultifies the spiritual aspirant who comes to view religion less as a means of freedom in self-transcendence from their limited ego—with its ever present concerns for status, prestige, and comfort—but rather as a manner of manipulating ones inner and outer energies to more deeply plunge into these spiritual dead-ends. Such a reckless syncretism, rather than enabling one to see his religion through the eyes of another and thus gain a deeper understanding of it as such, leads to something like a modal collapse of religious thought which in turn converts the entire endeavor into merely another tool used for therapeutic self-improvement.3 This voracious and consumeristic preoccupation with religion is of no help to anyone (except perhaps for a system that wants you to consume). While this philosophy aims at being respectful towards the religions it is taking bits and pieces from, it forms rather a supremely disrespectful attitude towards all religions failing to account for the fact that every religion is in a sense “complete” insofar as it contains within itself an inner coherence that is not convertible across confessional lines. For while a surface level analysis of moksha, paranirvana, and sotirios might conclude that these concepts are the same, any robust analysis and study into the topic reveals that not only are different religions often discussing different realities—they are also offering different outcomes.

While it does warm the heart to conceive of all religions as “aiming for the same place” it is misleading to conclude that because all religious traditions deal in some sense with the numinous that the goals towards which they aspire are synonymous. For example, the Buddhist, far from being honored by being told that his practice in realization of annata and the emptiness of all things is essentially the same to the Christian view of salvation or the Advaitan vision of moksha, is in fact scandalized by such intimations. For in his mind, such a vision of paradise or liberation would be completely inimical and counterproductive to his spiritual efforts presenting merely another obstacle in the path towards realization.

In fact, it is precisely because of this fundamental inconvertibility of one religious tradition to another that makes for a vision of “dual belonging,” that is so often prized by many Christian-Buddhists such as Paul Knitter, essentially impossible. While my goal here is not to debunk Knitter’s particular vision of dual-belonging or his “mutuality model”, I think it is important to mention it with regard to the three major ways of engaging in inter-religious dialogue: Exclusivism, Inclusivism, and Pluralism—and how these relate to St. Nikolai’s unique vision of inter-religious dialogue.

Dual-belonging, as understood through Knitter’s mutuality model, proposes a manner of Christian living in which one can, so to speak, “cross over” to another faith. In embodying this faith, with its requisite beliefs, practices, and way of life, one is capable of properly evaluating that religion on its own terms. Therefore, at the conclusion of this “crossing-over” one is then to cross back to their native tradition enriched with a full measure of wisdom from the other. I am not only sympathetic to this vision but, in part, heartily agree. Since a religion is an entire worldview, it cannot truly be understood from the outside as someone looking in. Much like someone who peers into an Orthodox temple and sees a dimly lit nave with walls marvelously adorned in iconography, he can never see the icons that are on the wall with the window he is using to peer inside. If he wishes to see the entirety of the temple, he must go inside and see it from within. It is for this reason that even the efforts I go to on this dispatch to have conversations across confessional lines are undertaken fully knowing that there are unknown unknowns I have yet to conceive of within another tradition.

While it may be possible for some to successfully go from one faith to another and return with a widened awareness and deepened understanding, I am unconvinced by its possibility for a number of reasons. First, and perhaps most importantly, this “cross over” leaves no room for the particularities of Christian (or any) faith to be retained in an orthodox manner that would be agreeable to the committed practitioners of that very faith. That is to say, belief in a tri-hypostatic God in whom we subsist, find our being, and will be reunited with at the parousia (i.e. the very bedrock of any confessionally orthodox Christian understanding of the faith) is already one that finds itself deeply at odds with the religious traditions one would be attempting to cross over to. For example, in what meaningful way could one retain their Christian conviction in the divinity of Christ as the second person of the Trinity while reciting shahadah in a way that is acceptable within an orthodox Muslim view? Such a crossing over would necessarily entail a total departure from one’s native soil into the uncharted waters of another faith severing them from their natal religion. This kind of departure already has a name: conversion.

Second, even if such a crossing over were theoretically possible in a way that was not a simple conversion from one faith to another, it would leave the individual doing this crossing back and forth in a precarious even perilous place. As Ernest Valea writes in his excellent essay, Buddhist-Christian Dialogue as Theological Exchange, quoting both John B. Cobb and Catherine Cornille who have written extensively on the topic of dual belonging within a Christian-Buddhist axis,

Cobb warns that once one crosses the bridge to experience Buddhism from within, he or she is “shut off from the Christian world.” A similar warning is expressed by Cornille, when she says that “There is often no ‘coming back’ from a deep identification with another religious tradition.”4

It would seem to be the case that such a crossing over, rather than giving one “insider information” from the other tradition, simply operates in the way any proper religion ought to by fundamentally re-wiring our perception of reality thus making a return to a previous way of thinking increasingly impossible. Of course, Valea’s, and by extension Cobb’s and Cornille’s, warning is simply that of experts in the field of inter-religious dialogue who are by no means “spiritual authorities” on such complex matters. They concede that while such a transition is no simple feat it by no means makes it impossible to achieve successfully in theory. However, I think we ought to take such warnings seriously, particularly if we are to appropriately engage in inter-faith dialogue. None of us is as impervious to the allure we may find in other confessions as we might want to believe. Naturally, while I believe that the Christian revelation is not only complete but is the unique self-expression of God to mankind (not utterly dissimilar from other religions and yet in a sense transcending and including them within her embrace), I cannot dismiss the often equally attractive alternatives offered by other religions. In fact, to dismiss something outright perhaps makes one more susceptible to their draw and has led many to conversion away from Christ and to something other.

The third problem entailed with dual belonging and its accompanying mutuality model is that its epistemic grounding is fragile and rests on certain empiricist “value neutral” presuppositions about religion that are in reality illusory. Valea directly engages with Knitter’s analogy of dual-belonging as being like looking through multiple telescopes,

Knitter uses an interesting analogy to explain the need for a pluralistic approach in interfaith dialogue. If we look at the universe with our naked eye we will see only a tiny fraction of the multitude of stars and galaxies. To see more we need a telescope. This is what each religion does—it uses a telescope to have a better look at a particular realm of reality. But telescopes reduce the whole to a little portion of the sky. If we borrow another one’s telescope we will see another portion of it, and so on. The more telescopes we use, the more we understand what is out there. Likewise, diverse religious traditions build together a wider perspective on reality.5

The pluralistic perspective here seems attractive. Like a honeybee going to different flowers to drink from the nectar therein, the “dual-belonger” is simply using the telescope of another tradition to gain a deeper and fuller appreciation of the night sky. However, there is a dangerous yet subtle reversal that takes place. Valea continues,

Although this is a nice story, my study has shown that it does not apply to Buddhist-Christian dialogue. When followers of diverse religious traditions attempt to help each other to see more of the universe, the usual result is that they ignore or forget what they have originally seen with their own telescope, at which point the whole process really ceases to be truly pluralistic.6

This is most clearly seen in the fact that often those who attempt this crossing over to other religious traditions often “return” to Christianity with an ersatz vision of their indigenous Christian beliefs and practices instead of the promised increase in depth and maturity. All too often I see that these practitioners leave behind the “exclusivism” and “rigidity” of their former Christian faith only to replace them with an Eastern variation of rigidity and exclusivism that is papered over by a panache of inclusivity, enlightenment, and compassion. Valea finishes writing,

Knitter fails to see that pluralism is itself a telescope and thus has its own limitations. His pluralist telescope made him ignore the particularities which make each religious tradition unique and even irreconcilable with other traditions. And finally, his conversion to Buddhism shows that he did not remain faithful to his own agenda of using supplementary telescopes for broadening his view of reality, for he came to ignore what he had first seen with his “Christian telescope.”7

Pluralism then becomes, in a word, a new dogma. Giving one the sense of superiority all while being dazzled by the illusion of being an “objective observer.” Not being God, we are incapable of standing on a neutral epistemic ground (which, to be clear, does not exist) upon which to gaze down upon the various religions with an unconditioned birds-eye view. Therefore, all we are left with is another telescope, with all its foibles and narrowness, by which we can observe the same night sky like everyone else. And it is in ignoring the particularities of each religion that we find the incompatibility of pluralism with a genuine striving towards mutual understanding in inter-religious dialogue. For if we attempt to elide and erase legitimate differences, we are no longer undertaking the difficult task of understanding. Rather, we are reshaping the other into an image that is more agreeable to our own.

What then is the solution? While pluralism seems to be a dead end when engaging in a genuine inter-faith dialogue, neither can we retreat to an unenlightened and wooden exclusivism that dismisses dialogue outright. Exclusivism requires that we ignore the beautiful, the good, and the true that we undeniably find in other religions based on a prior intellectual commitment we have formed based on their utter reprobation. Or, as some kinder exclusivists propose—we engage in dialogue so as to learn as much as we can to “disprove” their systems in favor of our own. Despite this, the perceived middle-way of inter-religious dialogue, inclusivism, while more salutary in principle tends towards the paternalistic insofar as positing that all other religions are inferior paths by which one can come to understand the unique character of the inclusivists’ religion. By this understanding, Christ is teaching the same Dharma as Buddha, only that his claims of divinity and the eternality of God are merely “useful means” used to speak at the appropriate level of the Jewish people that must eventually be let go of in order to understand the truer “realities”8 of annata, annica, and shunyata. The Dalai Lama’s own position reflects the inclusivist perspective in which a virtuous Christian, Jain, or Muslim can, in theory, be reborn into the Tushita heaven. However, as both heavens and hells in Buddhism are also impermanent, his ultimate destination will be rebirth as a Buddhist. Any other birth would lead to a constraining ignorance keeping him bound to the five aggregates he must ultimately disidentify with.

Perhaps first and foremost, as is true of making any good beginning, humility must be at the heart of our engagement with other religions. This may perhaps seem obvious but acknowledging that there is much more to the world and to ways of being than what can be caught within our ken is a difficult often life-long process of realizing. Therefore, it is to seek to learn, as far as possible (fully accepting the fact that we can never comprehend, in toto, another religion we are not part of), what is being taught without first transposing it into an indigenous grammar that is intelligible for the one being taught. For example, moksha is unhelpfully rendered as “salvation” by many. This is misleading insofar as it fails to reckon with the ontological and theological divergences that arise from the system in which these terms are used. Moreover, moksha itself, much like salvation, means different things to different Hindus, Jains, and Buddhists. In like manner, if one asked a Reformed Calvinist, a Roman Catholic, and an Eastern Orthodox what “salvation” means one would likely get significantly different answers.9 No tradition is, in itself, univocal. As such, reading any one teacher or proponent of it by no means offers the full scope of that tradition’s breadth or explanatory capacity. Much in the same way that reading Ulrich Zwingli is not representative of 2000 years of Christian belief and practice.

In light of this complexity, I return to St. Nikolai’s prayer by the lake as I believe that what is found in this poem is perhaps a way forward. What is telling about this prayer is that Nikolai never seeks to justify or couch his praise for the teacher, leaders, and prophets of other religions in ways that are amenable to a pearl-clutching Christian. Indeed, what is conscientiously consistent throughout the poem is a theme of gratitude for the way in which God provides mankind with so many ways to come into virtue and, as he states, “full reality.” Most importantly, St. Nikolai’s chief admonition is to “Not slay the prophets sent to you, my soul, for their graves contain not them, but those who slew them.” As if pre-emptively addressing an exclusivist model of inter-faith dialogue, Nikolai reminds us that when we reject those who bear the truth we not only reject the messenger but He Who sent him, and therefore our very life. In this, perhaps Nikolai, rather than providing a comforting message about the beauty of all religions, is making a somewhat sobering point. The soul has received countless messengers who speak to her from time immemorial. So then, none of us is truly ignorant of the words of life. We must all stand before the dread judgement seat and make an account for the deeds we have done based upon what we have done with the wisdom given to us by the Prophets.

For we are, as Nikolai writes, called to cultivate within ourselves “virginity of the soul” that is itself “only semi-reality in a world of shadows.” This virginity of soul seems to be something like humility. Acceptance that we cannot see the whole picture; we cannot see as God sees. But that even this virginity is merely “A semi-reality—until God is born within her. Then the soul becomes a full reality.” Because to genuinely experience truth we cannot grasp it with our own power and our personal cultivation of virtue. While many traditions dismiss the need for “other power” as the way to achieve the goals of their spiritual path, there is no denying that we all need someone to, at the very least, introduce us to the path. We all enter into this world under a veil of ignorance, and we all need someone to lift it, if for a moment, to begin to undertake the great struggle of the spiritual life.

As a Christian it appears to me that while we know that Christ has “The words of eternal life”10 we cannot dismiss the wisdom of the prophets of all the earth’s people. We must, at the last be wise “And cordially receive the precious gifts of the wise men from the East, intended for your Son.” While this final verse may sound as though Nikolai is moving towards the paternalistic inclusivism I outlined above, I would suggest that perhaps Nikolai is no longer speaking to these other prophets—the wise men of the East, and is instead speaking to the Soul. In this, he returns to his tradition after seeing wisdom, light, and understanding and whispers now intimately in his own way to those who are, so to speak, “within” the fold. No more is Nikolai speaking to those without. Much like the wise men of the East who after following the star enter into the mystery of the cave to experience a true darshan11 of God and thereby offer their gifts to him and the Queen and Mother. Perhaps when we discover wisdom, we too must enter the cave of mystery, be silent, and with great care share such wisdom with others in our own religious halls.

Maybe this is a way of understanding the distinction of esoteric and exoteric in a non-gnostic fashion. When we engage with those outside, it is as eager children excited to learn and receive truth regardless of the source. As St. Jerome wrote, quoting from Jeremiah the Prophet, “There are many ways, and the many ways lead to the one way. Wherefore it says in Jeremiah: ‘Stand beside the ways of the Lord, and ask for the ancient paths. Find the one way, and walk in it’… Through many ways, we find the one way.” Therefore, when we have found the Way in the midst of the many ways we are to with great care and secrecy carry it back within as a means of returning our souls to their Original Purity, sharing with great gentleness and humility what we have discovered. This then becomes a way of truly sharing and always learning. This puts us in a position where we need not abandon or alter our own tradition from within, while also no longer needing to bend our faith out of shape to fit a mold that it was never meant to fit. It frees us from the endless preoccupation that all must convert to my religion lest they be left utterly bereft of saving knowledge, while also giving us the courage to look once again at the cross and see in it something truly unique, original, and saving that “Draws all men”12 to itself.

Saint Nikolai Velimirovich, Prayers by the Lake. Trans. Right Reverend Archimandrite Todor Mika and Reverend Doctor Stevan Scott. Grayslake, IL: New Gracanica Bookstore, 2020. pp. 86-88

1 Corinthians 8.1

One need only look at the rise of this syncretic approach within the “wellness industry” that has taken venerable contemplative traditions and has morphed them into techniques for psychological and physical improvements usually on the order of “maximizing industriousness,” further feeding an economic machine that has little, if any, interest in our spiritual wellbeing.

Ernest M. Valea, Buddhist-Christian Dialogue as Theological Exchange: An Orthodox Contribution to Comparative Theology (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2015) pp.90

Ibid. 93

Ibid.

Ibid.

And if we take the Zen route of Buddhist understanding of shunyata, we must apply the methodology of emptiness recursively on even these terms. No-self, impermanence, and emptiness are all themselves empty. To “hold on” to these concepts too tightly itself becomes an obstacle for enlightenment, which for the Zen master is not a state to be achieved, as is the case in Theravada Buddhism, but an already present reality that must be manifested i.e. zazen is enlightenment.

This is true even as one enters within each specific subgroup in any particular religion. Within Orthodoxy itself there are many “ways” of explaining what salvation is. Some may even seem outright contradictory. However, as is often the case, when discussing the Infinite, our paltry explanations are but mere fingers pointing to the moon.

John 6.68

Sanskrit term for “showing” “vision” or “appearance” of the murti in a Hindu temple.

John 12.32